There’s something about a sacrifice that can be incorrect. There is something about a sacrifice that can be correct. One of the things we saw was that Cain’s sacrifice, whatever it was, was wrong, and Abel’s was right. One is, well, what’s the proper sacrifice? Now, we already talked about that a little bit in regards to Cain and Abel. Two questions immediately rise from that. The hypothesis is that sacrifice is necessary to ensure that the future is safe, secure, productive, positive, and all of those things. But there’s a twofold problem that branches off that. So anyways, there’s the twin problem of getting the whole idea of sacrifice up and running, and then figuring out exactly what it means. We’ve figured it out, and it’s hard for people to make sacrifices, because, of course, the present has a major grip on you, as it should, because, in some way, you live in the present. It took a long time for people to figure this out. It’s the equivalent of the discovery of the utility of work. It’s the equivalent of the discovery of the future. One of the themes that I’d like to explore tonight, especially in relationship to the sacrifice of Isaac, is that once humanity had established the idea that sacrifice was necessary to move ahead-which is, really, a discovery of incalculable magnitude: the idea that you can give up something in the present and that will, in some sense, ensure a better future. It’s dramatizing the idea that you have to give up a part of yourself for the sake of the whole, and eventually, well, by modern times, that becomes virtually completely psychological in its essence, in that we all understand-perhaps not as well as we should, but at least well enough to explain it-that it’s necessary to make sacrifices, to move ahead in life. Second, it’s signified by the sacrifice of a part of the body for the sake of the whole. First of all, it’s giving up something concrete.

But I see its introduction as a step on the road to the psychologization of the idea of sacrifice. Now, there’s every bit of evidence that other cultures were utilizing circumcision beforehand, so it wasn’t necessarily a novel invention of the Abrahamic people. We’ll see, because one of the things that happens is that, when God makes his covenant with Abraham-this is the next part of the story-it’s also when the idea of circumcision is introduced into ancient Hebrew culture. I said, already, that these things are often first portrayed very dramatically and concretely before they become psychologized. I believe that’s what the sacrifice routines in the Abrahamic stories dramatize. It’s necessary, in some sense, to stay light on your feet, and also, I think, to renew your commitment to your aim upward. That chaos puts you in a state of psychophysiological emergency preparedness, chronically, and that just ages you. I think that’s in large part because, if you don’t dispense with your life as you move through it, then the stress of all that undone business, and of all those unmade decisions turns into a kind of chaos around you.

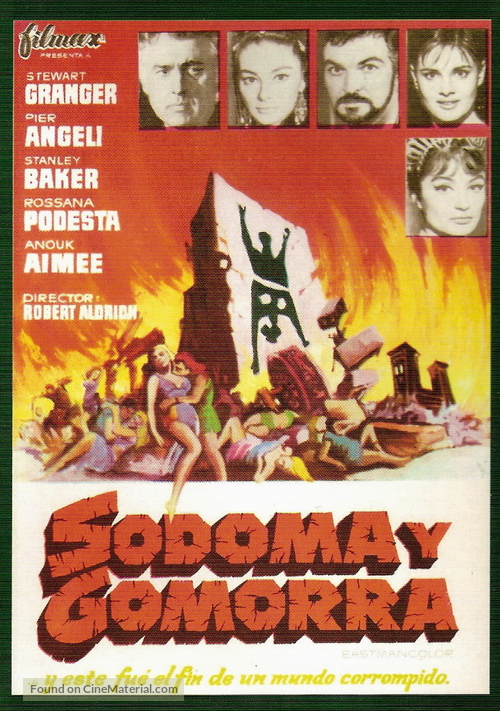

Otherwise it accretes around you, holds you down, and you perish sooner than you should. Part of that’s because, as you move through your life, you have to shed that which is no longer necessary. I was making the case that that’s a good time to make necessary sacrifices. And then, when you run that goal to its end, when that stage comes to an end, then you have to regroup and orient yourself once again. We were hypothesizing that you set out a goal for yourself, in your life-it’s like a stage in your life. The story of Sodom and Gomorrah is plenty complicated, too.Īll right, so what we established last week, at least in part, was this idea that the Abrahamic narratives are set up as punctuated epochs in Abraham’s life. So we’ll try to make some headway with that. We’re going to talk about the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, and then the story of the sacrifice of Isaac, which is an extremely complicated story. My plan is to get through all three of them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)